The Soviet era, particularly under Stalin’s reign, is often associated with oppression, fear, and hardship. However, after Stalin’s death, a gradual thawing occurred, and life for ordinary people in places like Soviet Estonia began to take on a semblance of normalcy. We mustn’t forget that the country was filled with ordinary people who needed to work, eat, drive and entertain themselves. In this blog post, we delve into the daily life in Soviet Estonia, exploring how their ordinary experiences differed from what we see today.

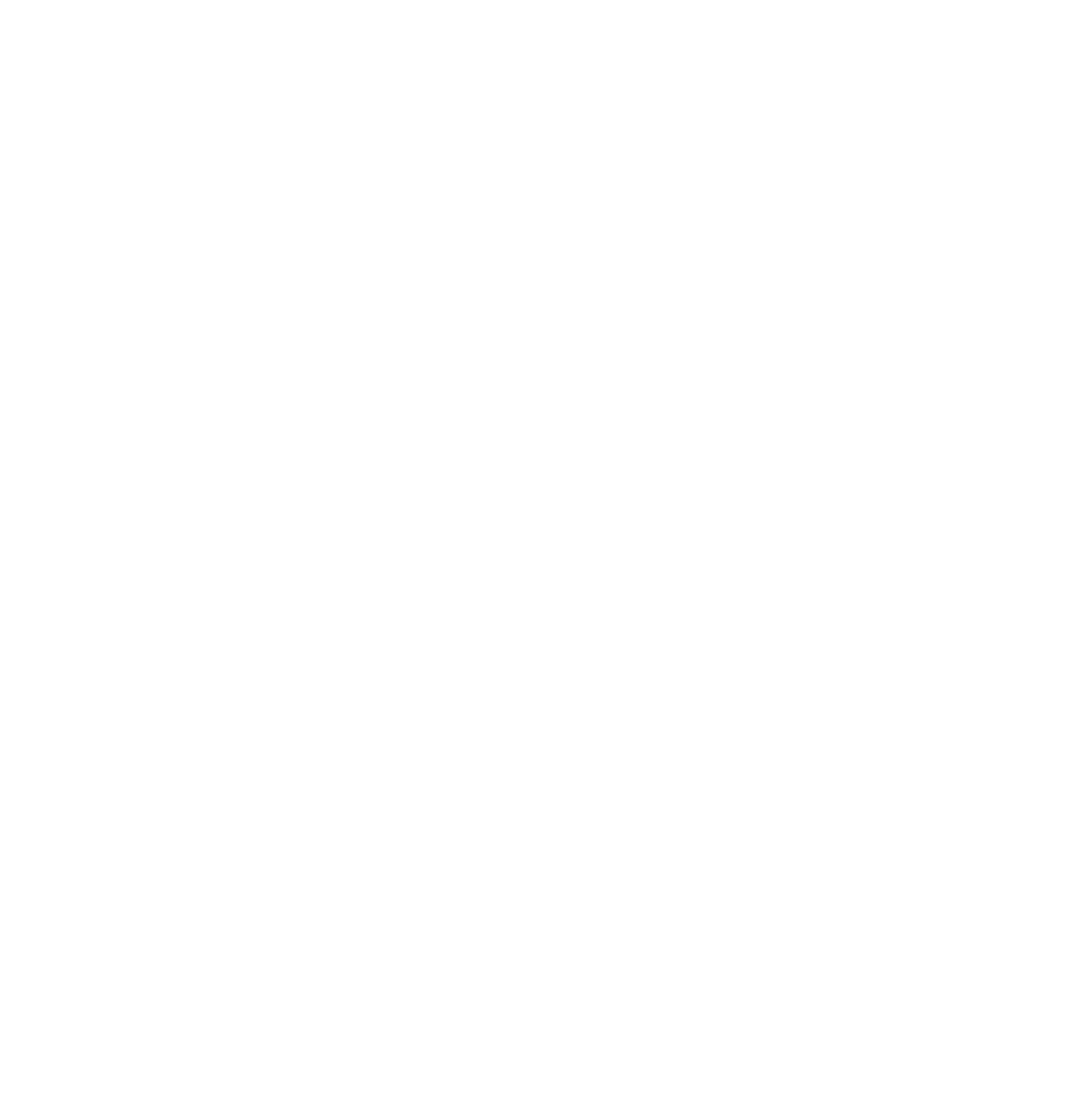

Cars: Navigating the Roads of Scarcity

It was pretty rare for people to have their own cars in the Soviet days. If you wanted to fulfil your dream of automobile ownership the first thing you needed was ‘car buying permission’. Yes, a document that gave you permission to go to the shop and buy a car. These permits were often handed out by your employer and involved background checks, lengthy waits and sometimes ended with rejection. Of course, it was the Soviet Union, so if you had the right contacts you could ‘fast track’ the process.

These permits were so sought-after that people would often skip the purchase and just sell the paperwork to someone else for a sweet profit. Another miracle of Soviet car buying is that second hand cars were much more expensive than brand new ones! Prices for automobiles were set by the state but your neighbour had no need for such restrictions (or official permission from the buyer), so they could ask for inflated prices. The free market alive and well in Soviet Estonia!

Media: Watching Finnish TV in Soviet Tallinn

In Soviet Estonia, media outlets were tightly controlled by the state, serving as tools for propaganda and ideological indoctrination. Access to foreign media was restricted, and censorship was pervasive. Tallinn, however, was in a unique geographical position, only 80km away from Helsinki. After a huge TV antenna was installed in the Finnish capital it was possible for Tallinn residents to watch Finnish TV. In this clip from Disco and Atomic War, a resident describes how he and his family were hooked on the American TV show Dallas!

Naturally, the Soviet authorities were not happy about this and attempts were made to stop the indoctrination from western media.

Speaking: was the Estonian language repressed?

During the Soviet era, efforts to Russify Estonia led to the suppression of the Estonian language in favour of Russian. The Estonian language wasn’t completely prohibited though, as these Reddit users commented:

“[Estonian language] wasn’t repressed per se (it was worse in Czarist era, 19th century) but the official language was Russian, the Russian officials and migrants spoke Russian, and to deal with the state apparatus and everyday life, you needed Russian. Singing songs in Estonian language wasn’t prohibited, although it depended on which songs of course — politically incorrect songs would get people in trouble.”

Estonia during the Soviet occupation (Reddit)

“The nationality part [of the Estonian language] was repressed and the Soviets didn’t want us to sing our national songs, about Estonia, it had to be connected to socialism somehow. A lot of the times, poets and composers used hidden meanings in their texts and music, so that the people could still be proud Estonians, but the censors didn’t have a clue of it. Sven Grünberg composed this amazing piece of music for the film “Hukkunud alpinisti hotell” “Dead Mountaineer’s Hotel”. He deliberately made up gibberish as lyrics, so it wouldn’t be dubbed in Russian as was the necessity of the censorship. He knew that it would destroy the vibe of the music.”

Explore Soviet Tallinn with Me!

If you’re curious to dive deeper into Tallinn’s Soviet past, why not explore it with me on a private walking tour? We’ll visit key locations, uncover hidden stories, and get a real sense of what life was like behind the Iron Curtain. Whether you’re a history buff or just love discovering the past in a personal, engaging way, this tour is designed to bring the Soviet era to life. Book your private Soviet Tallinn tour below!

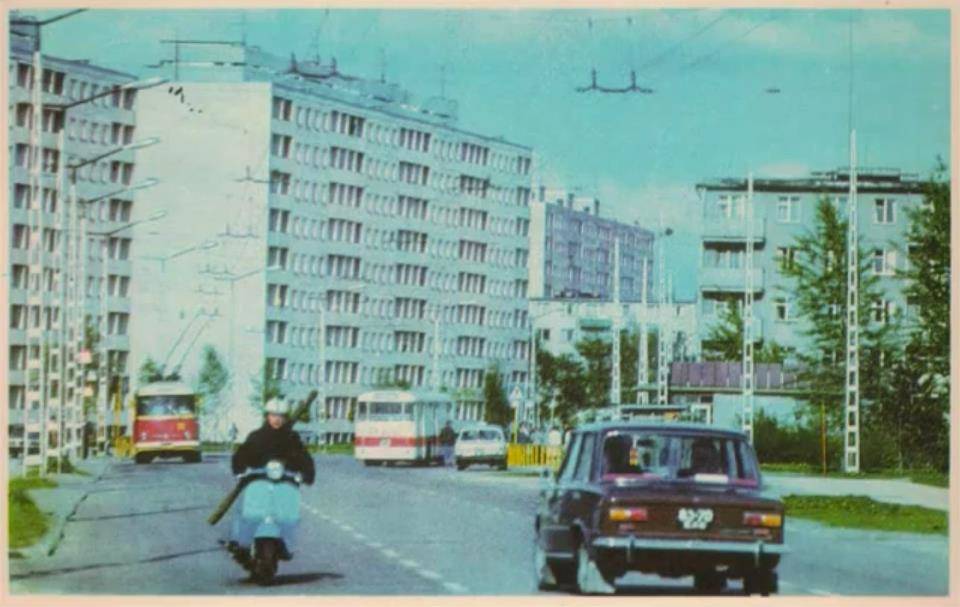

Going on holiday in Soviet Estonia

The mainstream holiday activites for many Estonians was retreating to their summer houses in the countryside for grilling, sauna and drinking (some things never change!). Soviet holiday resorts also popped up around the coastline as well. You can discover the abandoned remains of many of them today. While travel outside of Soviet countries was challenging, it was not entirely impossible. Travel groups were often organised by workplaces or companies, with vouchers given to exemplary workers or individuals connected to human resources bosses. These groups would journey to destinations like Czechoslovakia or Crimea. However, independent travel was rare but feasible, as evidenced by instances where individuals drove their own vehicles, such as LADA cars, to places like Crimea.

Travel to capitalist countries required a valid reason, such as scientific studies for university scholars. While not commonplace, some individuals managed to visit relatives in countries like the USA and Canada, albeit with considerable difficulty.

The Estonian coastline posed unique challenges due to its status as a border zone with the USSR. Special visas were required for travel within these zones, making activities like swimming along the coastline restricted to designated beaches. Despite these limitations, relaxation of travel restrictions occurred in the 1980s compared to the stricter controls of the 1950s and 1960s when the KGB monitored fishing settlements very closely.

Theft in Soviet Estonia

Soviet attitudes towards stealing were very peculiar. Theft from factories was rampant during Soviet period but in many cases it wasn’t even considered ‘stealing’. In the Communist system, everything was owned by everyone, so technically, if I need some wooden planks for some home DIY and I take them from work, I’m simply taking ‘my share’ of the common land. Surely that can’t be a crime? Stolen items could also be exchanged among neighbours in return for something more useful. You need paint for your house and I need some tools; perfect, let’s swap! This was a normal part of Soviet life.

Stealing from the state in order to sell though was a completely different ball game. This was considered a high level crime and if you were caught selling stolen items you were in for a pretty severe sentence, including years of hard labour.

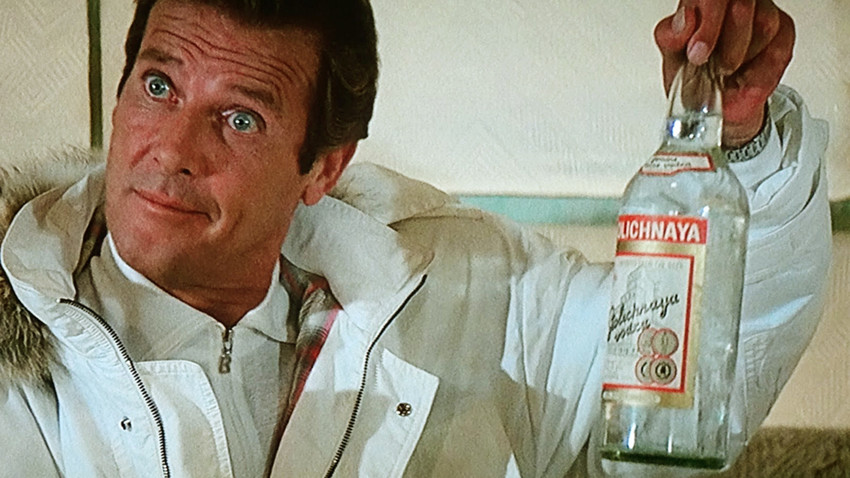

Vodka as the main currency

If you worked in a Soviet factory, you might think that rubles would be your main tool for getting something you need, but you would be wrong. Vodka was the main currency inside the walls of a Soviet factory. This beautiful substance was sneaked into industrial territories on a daily basis. Workers would exchange this valuable commodity for tools, mechanical parts, favours and almost anything else they needed. Despite being prohibited in the workplace, every factory had its own unofficial supply chain and workers were able to slip past security pretty regularly. If you owned the keys to the spirit warehouse, you were a very powerful guy!

Propaganda and Soviet Imagery

Soviet imagery permeated everyday life in Estonia, with portraits of Lenin and Stalin adorning public spaces and government buildings. Propaganda posters extolled the virtues of communism and glorified the achievements of the Soviet regime. These images were such a big part of daily life in Soviet Estonia that many would have become desensitised to these images glorifying their leaders.

In his documentary Hypernormalisation, Adam Curtis described the typical response of Soviet citizens to the propaganda they received in the 1970 and 1980s. A party official would talk about record levels of prosperity. The people watching the report would know that this wasn’t true. They could see it with their own eyes. The party official would know that they knew it wasn’t true, but everyone would just shrug, take another sip of their tea and say “okay, sure, if you say so”.

Pepsi and Coca-Cola in Soviet Estonia

Believe it or not, both Pepsi and Coca-Cola were available in Estonia during the Soviet days!

Pepsi and the Soviet Union trace their relationship back to the American National Exhibition in Moscow in 1959. At this event, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev famously sampled Pepsi, marking the first introduction of the soft drink to many Russians. This encounter proved to be a pivotal moment for the brand’s expansion into the Soviet market. By 1972, Pepsi had negotiated a cola monopoly in the USSR, trading cola syrup for Stolichnaya vodka to distribute in the United States.

By the late 1980s Pepsi had even brokered deals involving submarines and warships in exchange for cola! The company had a considerable presence in the Soviet Union. Read more of this fascinating story here.

As for Coca-Cola, who could forget about the famous ‘White Coke’? This clear beverage was credited to Soviet war hero Marshal Georgy Zhukov in the 1940s. To avoid any connection to its American origin he ordered the beverage to resemble vodka both in appearance and packaging. Coca-cola obliged and this covert drink was born.

The ‘real’ Coca-Cola found its way into Soviet Estonia, because it was one of the official sponsors of the Olympic Games in 1980. Tallinn hosted the sailing events for the Games so for the first time, this symbol of American imperialism was available to Estonians. McDonalds and many other famous western brands would follow several years later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union.